The Thing about the E-6 Visa-Industrial-Complex Nobody Tells You About

Sofia Martinez arrived at Incheon Airport on a Tuesday morning in March with two suitcases, a portfolio of editorial work from Bogotá, and a contract promising her an E-6 entertainment visa within eight weeks. She was twenty-three years old, tall and striking with dark hair that fell past her shoulders, and she had that particular combination of beauty and ambition that makes modeling agencies take notice. The Korean agency had found her through Instagram, messaged her for three months, and finally made an offer she couldn't refuse: accommodation, guaranteed bookings, and—most importantly—they would "handle everything" for her work visa. The contract promised they'd take a 40% commission on her earnings, which seemed standard based on what she'd read online about Korea's modeling industry.

Three months later, Sofia was still in Korea. But she didn't have a visa.

Instead, she had a growing list of expenses charged to her account by the agency: "document preparation fees," "expediting charges," "translation costs," "government liaison services." The total had reached ₩2.3 million—roughly $1,700 USD. When she asked to see the actual visa application, her agency contact became defensive. "These things take time," they told her. "The process is very complicated. You need to trust us."

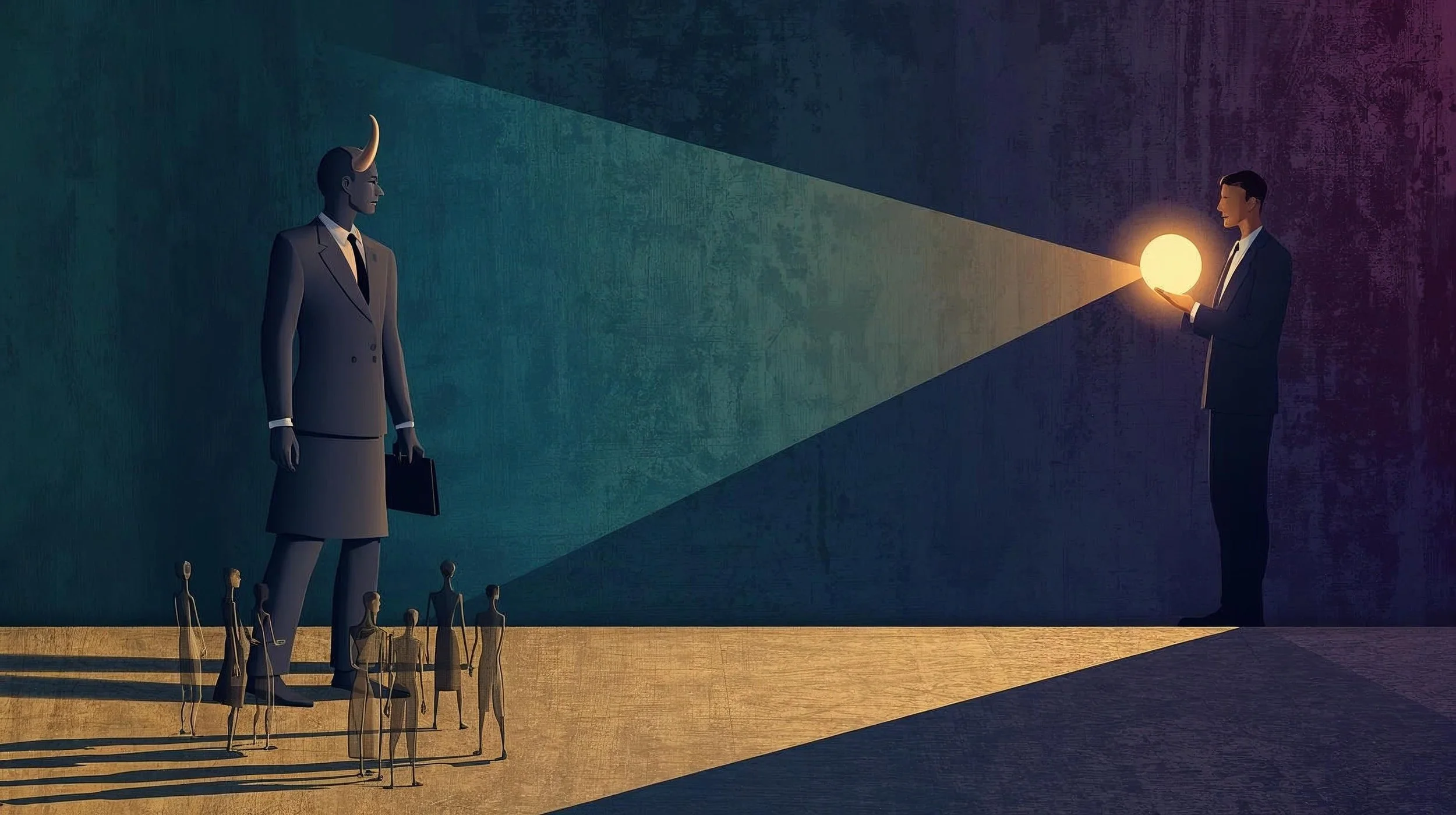

Sofia didn't know it yet, but she had walked into one of the oldest traps in Korea's entertainment industry. Not a scam, exactly. Nothing technically illegal was happening to her. But she was being systematically exploited through something economists call "information asymmetry"—and by the time she understood what was happening, leaving would cost her everything she'd invested.

The question is: why does this keep happening?

2.

Information asymmetry is a deceptively simple concept. It occurs when one party in a transaction has significantly more knowledge than the other—and uses that knowledge gap to profit. The classic example is used car sales: the seller knows exactly what's wrong with the vehicle, while the buyer can only guess. The information gap itself becomes valuable.

In 2001, economist George Akerlof won the Nobel Prize for describing how information asymmetry distorts entire markets. His famous paper on "lemons"—bad cars masquerading as good ones—showed that when buyers can't distinguish quality, they assume everything is low quality and adjust their offers accordingly. Good sellers leave the market. Bad sellers stay. The whole system degrades.

But Akerlof's insight applies far beyond used cars. It explains mortgage-backed securities that crashed the economy in 2008. It explains why healthcare costs spiral beyond comprehension. And—though this receives far less attention—it explains exactly what happens to foreign models and entertainers arriving in Korea with dreams of work and no understanding of the visa system they're entering.

The E-6 visa isn't mysterious. It's paperwork. A work permit specifically designed for foreign artists and entertainers working in Korea. The requirements are clearly listed on the immigration website. The processing time is standardized. The government fees are fixed and published.

So why do so many foreign entertainers end up in Sofia's position—confused, exploited, trapped?

Because their agencies profit when they don't understand the system.

3.

The pattern repeats itself with remarkable consistency across Korea's entertainment industry.

A model from Colombia arrives with a contract. A singer from the Philippines gets recruited through Instagram. A dancer from Ukraine signs with an agency that promises comprehensive support. The details differ, but the structure is identical: a foreign entertainer with dreams of work in Korea, an agency that promises to "handle everything," and a visa process that somehow becomes exponentially more expensive and complicated than it should be.

Immigration lawyers who work with foreign residents see these cases constantly. It's one of the most common problems that foreign entertainers face—not outright fraud, which is relatively rare, but systematic overcharging justified through deliberate mystification of a straightforward process. The problem is well-documented enough that in late 2024, a YouTube video addressing foreign models specifically highlighted "agency practices of charging visa fees and exploiting foreign models" as one of the key challenges in Korea's modeling industry. Foreign entertainer communities on Facebook and Reddit regularly post warnings about agencies that seemed legitimate at first but "became shady overnight"—a phrase that appears so frequently it's almost a template.

The first few times you encounter it, you might assume it's just incompetent agencies who don't know what they're doing. But then you start seeing patterns in which agencies use which excuses, which fees appear at which stages of the process, which explanations are offered when entertainers ask questions.

And you realize: this isn't incompetence. This is a business model.

The business model works like this: Keep the visa process mysterious. Never explain requirements in detail. Add fees at each stage without itemization. Create artificial dependencies by claiming special relationships with immigration officials. Position the agency as the irreplaceable gatekeeper to something complicated and bureaucratic that the entertainer couldn't possibly navigate alone.

The genius of the system is that it operates entirely within legal boundaries. Korean law doesn't regulate most of what agencies charge as "services." There's no fraud, technically. The entertainers sign contracts. They agree to the fees. Everything is documented.

But when one party understands the E-6 visa process completely and the other party understands nothing, calling it a fair transaction requires a particularly creative definition of fairness.

4.

Here's what the E-6 visa actually requires.

First: proof of expertise in your field. For models, this means a portfolio demonstrating professional work. Not amateur photos. Not Instagram selfies. Actual published editorial work, runway experience, or campaign credits. The standard is lower than agencies claim—you don't need to be internationally famous—but higher than complete beginners can meet.

Second: an employment contract with a registered Korean company. This is usually the agency itself, though it can be any registered entertainment business. The contract must specify salary, work conditions, and duration. It's binding on both parties.

Third: educational credentials. Not always required for models, but increasingly common. Either proof of modeling school, arts training, or relevant university education. A high school diploma usually suffices as baseline education.

Fourth: health check. Tuberculosis screening, drug test, blood work. This costs about ₩100,000 at designated hospitals and takes two hours.

Fifth: criminal background check from your home country. Apostilled or authenticated, depending on whether your country is part of the Hague Convention. This is genuinely complicated if you don't know the process, but it's also something you can arrange yourself for ₩50,000-₩150,000 depending on your country.

Sixth: passport photos meeting specific requirements—size, background color, recency. About ₩15,000 at any photo shop.

Total government filing fee for the E-6 visa: ₩100,000.

Add it up. ₩100,000 for the health check, ₩100,000 for government processing, maybe ₩150,000 for the background check if you need a service to help, ₩15,000 for photos. You're at ₩365,000—roughly $270 USD.

Sofia had been charged ₩2.3 million.

The difference—about ₩1.9 million—is what information asymmetry costs.

This markup pattern isn't unique to E-6 visas. Korean government agencies have issued multiple warnings about visa-related scams where applicants are charged "10 times higher than the official fee" through illegitimate services. In 2022, a Korean resident filed a complaint after discovering he'd used a fake K-ETA website that charged ten times the official ₩10,000 fee. The Korean Foreign Ministry felt compelled to explicitly state on its website that it has "not designated any application agencies" for visa services.

Sofia's ₩2.3 million charge for a ₩400,000 process represents a 5.75x markup—actually less extreme than documented visa scams operating in Korea, but following the exact same playbook: exploit information asymmetry, add mysterious fees at each stage, keep the applicant confused about what's actually required.

5.

The critical question is: how do agencies justify these fees to themselves?

Ask an agency director and they'll explain that the raw costs miss the point. Yes, the government fee is only ₩100,000, but what about the expertise required to prepare documents correctly? What about the relationships with immigration officials that smooth the process? What about the risk they're taking by sponsoring a foreign entertainer who might violate their visa? And—this argument sounds most reasonable—what about the significant labor involved in actually preparing all this paperwork?

These arguments sound plausible until you understand what they're actually describing.

"Expertise to prepare documents correctly" means filling out a form—in Korean, admittedly—that asks for standard information: name, birthdate, education history, employment details. If you've ever applied for a job, you can handle it. The form is available free on the immigration website.

"Relationships with immigration officials" is particularly interesting. In Korea's immigration system, there are no special relationships that expedite processing. Applications are handled in order. Processing times are standardized by visa type. No amount of knowing people changes this. When agencies claim special relationships, they're either lying or describing something they shouldn't be doing.

"Risk of sponsoring" is genuine—agencies can face penalties if their sponsored entertainers violate visa terms. But this risk is managed through the contract itself, not through inflated fees. If an agency is genuinely concerned about risk, they require deposits or bonds. They don't hide risk premiums inside mysterious "processing fees."

But the labor argument deserves serious consideration because it's actually true. Preparing visa paperwork does take time. Gathering documents, translating certificates, filling out forms correctly, coordinating with immigration offices—this is real work that takes real hours. Some agencies estimate it requires 10-15 hours of staff time per visa application.

Here's the problem with using this to justify ₩2 million in fees: that labor is literally what an entertainment agency does. It's not an extra service they're generously providing—it's the core function of their business model.

Consider how any other company handles employee paperwork. When McDonald's hires a teenager to work the register, someone in HR spends hours processing employment forms, tax documents, background checks, training schedules. This labor is real and time-consuming. But McDonald's doesn't send the teenager a bill for ₩1.5 million to cover "employee onboarding administrative costs."

Why not? Because that administrative labor is McDonald's cost of doing business. They profit from the teenager's labor at the register. The paperwork required to legally employ that teenager is their expense, not the teenager's.

The exact same logic applies to entertainment agencies. They profit from their signed entertainers—in Korea's modeling industry, agencies typically take 40-60% commission on all bookings. The visa paperwork that allows the entertainer to work legally in Korea isn't a favor the agency is doing for the entertainer. It's the agency's cost of acquiring talent they can profit from, often for years.

When you sign a model, you inherit the administrative work required to make that model legally employable. That's the deal. That's what agencies are supposed to do in exchange for their substantial commission on the model's earnings.

Charging entertainers inflated fees for visa paperwork is like McDonald's charging employees for the privilege of having their hiring forms processed. It fundamentally misunderstands—or deliberately misrepresents—the employment relationship.

What agencies are really selling isn't expertise or relationships or risk management or even labor. They're selling the solution to a problem they created: your lack of understanding of a deliberately mystified process.

6.

The most revealing moment in any agency-entertainer relationship comes when the entertainer asks to see the actual visa application documents.

Legitimate agencies respond immediately. They show you the form, walk you through each section, explain what information came from where. They provide copies of everything submitted on your behalf. They give you the tracking number so you can check status yourself on the immigration website.

Exploitative agencies deflect.

"You wouldn't understand it—it's all in Korean."

"We can't show you sensitive documents that are part of our proprietary process."

"Seeing the documents before approval might jinx the application."

"Our legal team doesn't allow us to share internal paperwork."

These responses sound almost reasonable in isolation. But notice what they all have in common: they position the agency as the exclusive holder of knowledge, the only party capable of navigating the complex system, the gatekeeper you must trust completely because you can't verify anything yourself.

This is information asymmetry weaponized.

Lee saw the pattern clearly after her years counseling foreign residents. "The entertainers who got exploited worst weren't the ones with the shadiest agencies," she says. "They were the ones who asked the fewest questions. The moment you accept 'just trust us,' you've given up the only leverage you have."

The leverage is simple: knowledge.

7.

Sofia's story had a turning point.

Four months into her stay in Korea, she met another Colombian model at a cafe in Itaewon. This model—we'll call her Carmen—had arrived six months earlier with a different agency. Carmen had her E-6 visa. She'd been working legally for four months. And when Sofia asked how much the visa process had cost her, Carmen looked confused.

"Like ₩400,000 total? The health check was the most expensive part. Why?"

Sofia told her story—the mounting fees, the vague explanations, the refusal to show documents. Carmen listened, then asked a simple question: "Did they ever actually file your application?"

Sofia didn't know.

Carmen introduced her to a Korean friend who worked in immigration law. The friend logged into the public immigration tracking system with Sofia's name and passport number—information any applicant can access—and within thirty seconds had the answer.

No application had been filed.

After four months and ₩2.3 million in fees, Sofia's agency had never submitted her visa paperwork.

8.

There's a term in behavioral economics for what happened to Sofia: "sunk cost trap." Once you've invested money, time, and hope into something, walking away feels like admitting defeat. You've already paid ₩2.3 million. You've already stayed four months. You've already told everyone back home about your exciting modeling career in Korea.

Leaving means losing everything and starting over.

So you stay. You pay more fees. You wait longer. You tell yourself it will work out because the alternative is too painful to consider.

Agencies understand this psychology perfectly. The longer they can keep you confused and invested, the less likely you are to leave. Each additional fee becomes easier to justify because of all the previous fees you can't recover. Each additional week makes starting over somewhere else seem less feasible.

The trap doesn't require physical coercion. It doesn't require locked doors or withheld passports—though some agencies do these things too. The trap is psychological, built entirely on information asymmetry and sunk costs.

And the trap works only as long as the information gap persists. The moment entertainers understand what the E-6 visa actually requires, everything changes. Suddenly they can ask specific questions. They can verify answers. They can hold agencies accountable. The whole power dynamic shifts.

This is why agencies fight so hard to maintain mystery around the visa process. The mystery is the product.

9.

Let's be clear about what we're describing here. This is not an exposé of criminal activity. Most agencies operating this way aren't breaking laws. They're exploiting legal gray zones where regulation is sparse and foreign entertainers have little recourse.

The contracts are real. The fees are listed—if vaguely. The services provided have some justification, even if wildly overpriced. Nothing here rises to the level of trafficking or fraud that would trigger criminal investigation.

But legal and ethical are not synonyms.

The problem has become widespread enough that the Korean government has explicitly acknowledged it. Immigration law firms now state matter-of-factly that "the Korean government has strengthened oversight of the E-6 visa program to prevent potential abuse and ensure better protection for foreign entertainers." Government agencies don't strengthen oversight of systems that are working well. They strengthen oversight when systematic exploitation becomes too obvious to ignore.

The question isn't whether agencies can operate this way under current Korean law. They obviously can—thousands do it successfully every year. The question is whether a transaction built entirely on deliberate information asymmetry can be called fair, even when all parties sign willingly.

Akerlof's research on information asymmetry focused on market inefficiency. When information gaps are large, markets fail to allocate resources optimally. Good products can't distinguish themselves from bad ones. Quality degrades. Trust erodes.

But there's another consequence Akerlof noted: information asymmetry creates deadweight loss—value that simply vanishes from the economy. Sofia's ₩1.9 million in excess fees didn't make anyone better off. The agency got money it didn't earn through actual service. Sofia got a visa she could have obtained for a fraction of the cost. Korean society got a foreign entertainer who started her career resentful and exploited rather than enthusiastic and empowered.

Everyone loses except the agency extracting rents from information they're withholding.

10.

The story has a final chapter.

Sofia filed a complaint with the Korean immigration office describing what had happened. Immigration officials investigated her agency and found—unsurprisingly—multiple violations of entertainment industry regulations. Not because of the fees, which exist in legal gray zones, but because the agency had accepted money for visa services without filing applications within the required timeframe.

The agency was fined. Sofia received a partial refund. She found a new agency—Carmen's—that processed her visa correctly for ₩450,000. She's been working legally in Korea for eighteen months now.

But here's what's interesting: Sofia's original agency is still operating. They're still recruiting foreign models. They're still charging similar fees. The fine was a cost of doing business, not a threat to their business model.

Sofia's experience was neither unique nor particularly extreme. It fell squarely within documented patterns of visa fee exploitation in Korea's entertainment industry—patterns widespread enough that by late 2024, they were being openly discussed in YouTube videos aimed at foreign models, documented in immigration lawyer consultations, and prompting the Korean government to explicitly acknowledge the need for "strengthened oversight of the E-6 visa program to prevent potential abuse."

Because the business model isn't about breaking laws. It's about controlling information.

11.

Jaewon Lee is an immigration lawyer in Seoul, slight and precise in her movements, with the careful diction of someone who spends her days translating complex legal concepts into language non-lawyers can understand. For three years, she volunteered as a pro bono lawyer at the Shindorim Foreign Residence Center—a government-run facility in southwest Seoul where foreign residents can get free legal counseling on immigration issues, labor disputes, and visa problems.

She heard Sofia's story forty-seven times.

Not literally Sofia's story, of course. The details changed—different countries, different agencies, different amounts owed. But the structure was identical. A foreign entertainer arrives in Korea with a contract. The agency promises to "handle" the visa. Weeks pass. Then months. The entertainer can't work legally, can't leave the agency without losing their investment, can't even verify what's actually happening with their application because they don't speak Korean and the agency won't show them the documents.

"The first few times, I thought it was just bad agencies," Lee says. "Incompetent people who didn't know what they're doing. But then I started seeing patterns in which agencies used which excuses, which fees appeared at which stages of the process. I realized this wasn't incompetence. This was a business model."

After leaving the Shindorim center, Lee did something unusual for an immigration lawyer. She started teaching workshops.

Not for lawyers—for foreign entertainers.

The workshops are straightforward. Two hours. ₩50,000. She walks through the entire E-6 visa process step by step. Shows the actual application form. Explains each requirement. Lists realistic costs. Demonstrates how to check application status online. Answers every question until no questions remain.

"The goal is simple," Lee says. "Eliminate the information gap completely. Make it impossible for agencies to profit from confusion."

Her approach is almost academic in its thoroughness, but the effect is practical. Entertainers leave her workshops with something more valuable than visa expertise—they leave with leverage. They can ask their agencies specific questions: "Why does document translation cost ₩300,000 when certified translation services charge ₩80,000?" They can verify claims: "You said you submitted my application three weeks ago—can I have the tracking number?" They can calculate whether fees are reasonable or exploitative.

Knowledge becomes negotiating power.

The workshops create a second effect Lee didn't initially anticipate: word of mouth. Entertainers talk. They share information. They warn each other about agencies charging ₩2 million for a ₩400,000 process. They recommend agencies that are transparent about costs and timelines.

Information asymmetry works only in isolation. Once entertainers start sharing knowledge, the entire ecosystem begins shifting.

12.

There's a broader principle here that extends far beyond Korean entertainment visas.

Information asymmetry flourishes in areas where expertise seems impenetrable to outsiders, where jargon creates barriers to entry, where the people with knowledge benefit from others remaining ignorant. Healthcare. Finance. Legal services. Immigration. Education consulting. Any field where experts can position themselves as irreplaceable gatekeepers.

The traditional response is regulation—governments step in to mandate disclosure, standardize pricing, require transparency. But regulation is slow, often incomplete, and difficult to enforce across complex systems.

Lee's approach suggests an alternative: radical transparency. Don't wait for regulators to force disclosure. Teach people what they need to know to protect themselves. Give them tools to verify claims. Empower them to ask the right questions.

This strategy disrupts not through legal force but through knowledge diffusion. When enough people understand a previously opaque system, agencies that profit from confusion lose their competitive advantage. Transparency becomes the market differentiator—smart agencies adopt it willingly because informed clients become loyal clients.

The model is spreading. Other immigration lawyers in Korea have started similar workshops. Foreign entertainer communities now maintain online resources detailing visa requirements and warning about exploitative agencies. The information asymmetry that agencies relied on for profit margins is eroding.

Slowly. But measurably.

13.

Sofia's experience raises an uncomfortable question: if the E-6 visa process is relatively straightforward and entertainers are being exploited through information asymmetry, why doesn't the Korean government simply make the information more accessible?

The answer is: they have. Sort of.

The immigration website lists all requirements. Processing times are published. Fees are clearly stated. The information exists, freely available to anyone who wants to find it.

But—and this matters—the information exists in Korean. For foreign entertainers who don't speak the language, navigating government websites, understanding legal terminology, and verifying whether their agency is following correct procedures remains genuinely difficult.

This creates what economists call "rational ignorance." The cost of acquiring information—learning enough Korean to navigate immigration bureaucracy, understanding legal procedures, verifying every detail of your agency's claims—exceeds the perceived benefit of having that information. It's not that entertainers are lazy or incurious. It's that the investment required to eliminate information asymmetry seems impossibly large.

So they rely on agencies. They accept "trust us" as the only realistic option. They pay whatever fees are quoted because the alternative is trying to navigate a foreign bureaucracy in a foreign language in a foreign country where making mistakes could end their career before it starts.

The agencies aren't creating the information barrier. They're exploiting one that already exists.

This distinction matters. It suggests that blame doesn't lie primarily with exploitative agencies—though they deserve criticism—but with systems that make essential information practically inaccessible to the people who need it most.

Lee's workshops work not by translating government websites but by distilling essential information into actionable knowledge. Two hours. Plain language. Specific examples. Direct answers. The goal isn't making entertainers into immigration experts—it's giving them enough understanding to recognize exploitation when it's happening.

That's the threshold where information asymmetry collapses. You don't need complete knowledge. You need enough knowledge to ask dangerous questions.

14.

There's a telling moment in Lee's workshops that happens about forty minutes in.

She's explained the basic E-6 requirements. She's shown the application form. She's listed realistic costs. And then someone—usually several people—raises their hand and describes fees their agency has charged them.

"My agency charged me ₩800,000 for document preparation. Is that normal?"

"I paid ₩500,000 for 'priority processing.' Does that actually exist?"

"They told me I needed special insurance that cost ₩600,000. Did I really need that?"

Lee answers each question directly. No, ₩800,000 for document preparation isn't normal—document preparation means filling out a form, which takes an hour. No, priority processing doesn't exist for E-6 visas—applications are handled in order. No, you don't need special insurance—you need Korean health insurance once you start working legally, but that's separate from the visa application.

The room gets very quiet during these exchanges.

Because what's happening is that twenty or thirty foreign entertainers are simultaneously realizing they've been systematically overcharged. Not by a little. By multiples. They're calculating in their heads—₩1 million extra, ₩1.5 million, sometimes ₩2 million beyond what the visa actually costs.

Some people get angry. Some get quiet. Some start asking questions about contracts and refunds and legal recourse.

But everyone leaves understanding something they didn't understand before: the system isn't that complicated. Their confusion was manufactured. The mystery was the product.

That realization changes how they interact with agencies going forward. Not always immediately—many are locked into contracts that make leaving expensive. But eventually. When contract renewals come up. When they warn friends considering similar opportunities. When they share information in online communities.

Information asymmetry, once exposed, is very difficult to reimpose.

15.

Let's return to where we started: Sofia Martinez at Incheon Airport, two suitcases, a portfolio, and a contract promising things that wouldn't be delivered as promised.

The question we posed was: why does this keep happening?

Now we have an answer. It keeps happening because it works. Because agencies profit substantially from information asymmetry. Because foreign entertainers arrive in Korea without understanding the visa system, without speaking Korean, without networks to verify claims, and with strong incentives to believe agencies that promise to handle everything.

The exploitation isn't violent. It's not dramatic. It operates through contracts and fees and explanations that sound plausible if you don't know enough to recognize them as false. It's legal enough to persist and profitable enough to continue.

Sofia's experience wasn't exceptional—it was typical. The ₩2.3 million in visa fees, the mysterious delays, the refusal to show documentation, the mounting charges without itemization. These aren't aberrations. They're the standard playbook, documented across YouTube videos, Facebook groups, Reddit threads, immigration lawyer consultations, and government oversight reports. The Korean government didn't strengthen E-6 visa oversight because of one bad agency. They strengthened it because the pattern was systemic.

But—and this is crucial—it's also fragile.

Information asymmetry as a business model depends entirely on sustained ignorance. The moment entertainers understand what the E-6 visa actually requires, the entire system starts collapsing. Agencies can't charge ₩2 million for a ₩400,000 process once people know the real costs. They can't claim special relationships that don't exist once entertainers can verify claims. They can't hide behind complexity once the process has been demystified.

Lee's workshops aren't solving the problem alone. They're part of a broader shift toward transparency driven by technology—online communities, translation apps, accessible information—that makes sustained information asymmetry increasingly difficult to maintain.

The agencies charging Sofia ₩2.3 million for a visa that should cost ₩400,000 are operating on borrowed time. Not because regulations will shut them down—though eventually some might. But because their business model depends on information people increasingly have access to.

You can't profit from confusion indefinitely once people understand the system.

16.

The E-6 visa isn't complicated. That's the secret they're not telling you.

It's paperwork. Forms. Requirements you can list on one page. Costs that total a few hundred thousand won, not millions. Processing timelines that are standardized and publicly available.

What's complicated is navigating a foreign bureaucracy in a foreign language in a foreign country where you don't know who to trust. That's genuinely difficult. But it's not the same as the visa process itself being mysterious.

Agencies profit by conflating these two things—by taking your legitimate confusion about navigating Korean bureaucracy and convincing you that the visa process itself is impossibly complex, that only experts with special relationships can navigate it, that you have no choice but to pay whatever they charge and trust whatever they tell you.

Information asymmetry turns your confusion into their profit margin.

But here's what happens when you understand the actual requirements: suddenly you can ask specific questions. You can verify answers. You can calculate whether fees are reasonable. You can hold agencies accountable.

The power dynamic shifts completely.

You stop being a client who must trust and become a customer who can choose. Agencies that operate transparently—who show you the forms, explain the requirements, charge realistic fees—become obviously preferable to agencies that hide behind mystery and complexity.

The market corrects itself once information asymmetry collapses.

That's why workshops like Lee's matter. That's why foreign entertainer communities sharing information matter. That's why this article matters.

Not because any single intervention solves the problem. But because every bit of knowledge shared, every mystery demystified, every exploitative practice exposed, makes information asymmetry slightly harder to maintain.

Eventually—slowly, incrementally, imperfectly—the business model fails.

The E-6 visa isn't complicated. They just profit when you think it is.

Now you know.

Immigration lawyer Jaewon Lee conducts workshops on E-6 visa requirements for foreign entertainers in Korea. The workshops are held monthly in Seoul and are open to anyone navigating Korea's entertainment industry. For more information, visit lawyerseoul.com or register at forms.gle/yJcYsezj4zZwuaSN8.

EventJAN 19, 2026 | 2-4 PM

B1, 316 Bongeunsa-ro, Gangnam-gu, Seoul

Korea Gas Corporation Building

선정릉역 Exit 4 (2 min walk)

₩50,000